François-Régis Mouton

François-Régis Mouton

Could you tell us about the IOGP, its tasks and responsibilities?

The IOGP is the international industry association representing the upstream sector (Exploration & Production) of the oil and gas chain. Our Members – just over 80 companies today – account for more than 40% of oil and gas production worldwide and about 90% in Europe. Our goal is to make these operations ever more secure, responsible and sustainable. We do this by working to continuously improve HSSE, operational, and energy efficiency performances, as well as by publishing a collection of good practices in these fields. It goes without saying that to achieve this goal, we collaborate with national, regional and international bodies and regulators, such as the European Union and the United Nations Environment Agency.

Traditionally, the IOGP’s role has focused on the rather technical and operational aspects, but faced with the questions posed by the future role of our industry in the energy transition, we are also the spokesperson of our field in Brussels. Faced with a speech that is often too simplistic because of a lack of awareness – “we must break free from fossil fuels today” – we explain the continued evolution of oil and gas uses, the important role they will continue to play, even within the Paris Agreement, and the technologies we are developing to reduce our own emissions, those of our customers and those of other sectors.

What are the major projects to adapt your sector of activity to the energy transition?

There are three.

The first is the adaptation of our offer. The business portfolios of our Members are changing. The balance of oil and gas reserves of many majors leans more in favour of gas. Twenty years ago, drilling a well and finding gas was almost a failure – it was oil that the world economy needed most. Today, we are actively looking for gas because global demand for this flexible and less carbonaceous energy is exploding, as it is the perfect substitute for coal and the ideal complement to intermittent and eminently variable renewables in their electricity generation. We do not see much of it, but our industry also invests significant amounts in renewables, batteries, and the electrical sector in general. Their offer is expanding, and some are renamed “energy companies”, and no longer “oil & gas companies”, to mark the occasion.

Europe and our industry have now truly entered the era of “beyond petroleum” as Lord Browne had stated too early, but not in the era of “without oil & gas” as we all too often understand it: the energy transition opens opportunities, and we are also here to seize them.

The second project is the deployment of widespread low-carbon technologies other than renewables: I am mainly talking about hydrogen and carbon storage and capture (CSC). We capitalize on two advantages: natural gas is today the main “raw material” used to produce hydrogen for large-scale industrial needs. We can decarbonise gas by separating and storing the CO2 it contains and injecting hydrogen into the energy system. I now come to the second advantage – not only do we have the technology for capturing and storing CO2, but we also have hundreds of depleted and often offshore reservoirs that have proven their watertightness for millions of years and can therefore be used to store huge volumes of CO2 hundreds or even thousands of meters deep and over hundreds of years.

The third project is that of reducing our own environmental impact – right from the oil and gas production stage.

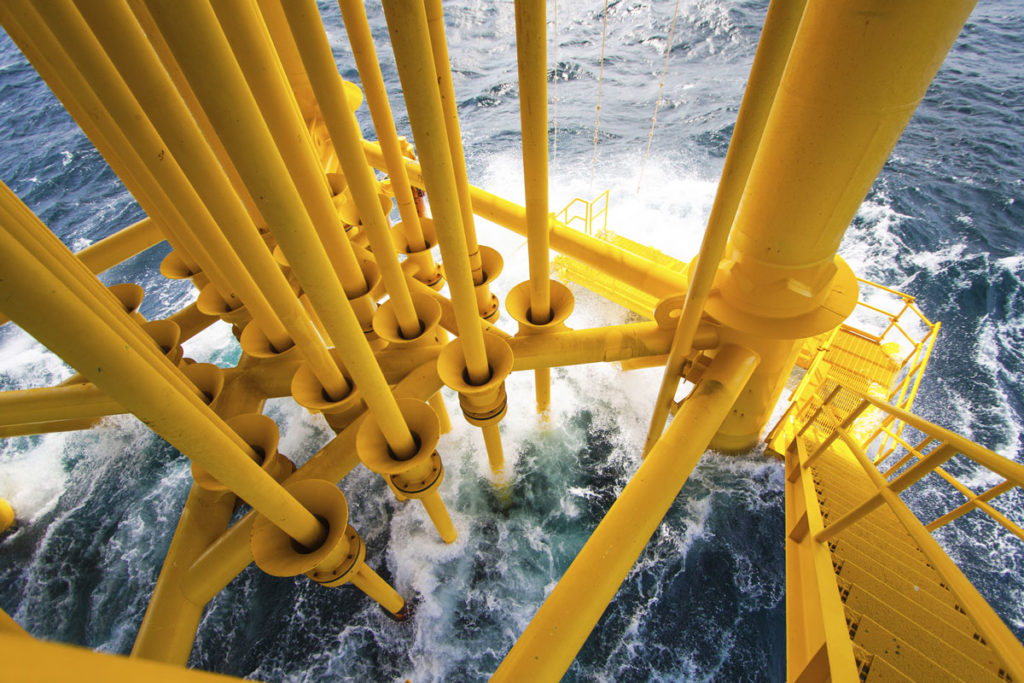

Today, for example, nearly three-quarters of platform emissions in the UK North Sea come from diesel or natural gas-powered electric generators. The idea is to replace them with electricity, and green when possible. This involves projects under consideration such as large offshore wind investments in the North Sea or even the wiring of platforms from the mainland.

But our industry is also working on what has been called in recent years the “leakage of methane”. We are well aware of this – if gas is to play a role in the transition, especially as a replacement for coal, it is crucial to minimize its own environmental impact. The industry has recently launched numerous initiatives to detect, measure, and reduce methane leaks. From infrared cameras to satellites, to drones, the means devoted to them by our industry are important. Within the IOGP, we are actively involved in this work – we look at what is working and what is less effective, and we draw up good practice recommendations for our Members.

How should the industry act to reduce its environmental impact? How about methane?

This requires recognition of the problem and flawless discipline. In the past, we have tackled the safety of our operations. Accidents were more frequent and more serious, as were their consequences – from an operational point of view, but especially from a human point of view. We have made it the number one priority: it has even become one of the company’s “values”. We have rethought our approach to safety as a whole and have devoted the necessary resources to it. Today, accidents have become extremely rare and we aim for the zero figure.

We do the same for methane. Through the “Methane Guiding Principles” initiative, for example, we start with awareness campaigns for our most senior field staff and decision-makers among our members. Then, in partnership with NGOs, academicians and specialists in the reduction of methane leaks, we actively train them to implement the means and adopt the necessary reflexes to solve the problem. We have started, we must now continue – our credibility depends on it.

What does the taxation of products (oil and gas) mean for member states today? And what can you say about the financial E&P contributions?

It is considerable, and relatively unknown! Each year, our products – crude or refined – represent a net contribution of around € 420 billion to EU member states + Norway, of which € 37 billion comes from E&P. To give you an idea, € 420 billion is the equivalent of almost 3% of the European Union’s GDP, or that of a country like Belgium or Austria!

We often hear NGOs talking about subsidies to our sector, but it’s absurd given what it taxes! In Europe, public intervention usually consists of less taxation for a category of customers in a precarious situation, or less on one product rather than the other – for example, diesel and gasoline until recently – or investment incentives, which ultimately earns enormously more than the supposed “cost” of the measure. The figures show that our sector has benefited from € 3.3 billion of public aid in Europe in one year – € 1 invested represents € 130 recovered!

But yes, there are indeed subsidies in less developed countries and regions, where without them, the population could not stay warm, have electric lighting or even move around. Do you think those who denounce these aids care?

In a carbon-neutral economy, how are the uses of oil and gas going to evolve?

It is certain that a carbon-neutral Europe is not likely to be a growth market for oil and gas. But we can choose to see things simply in terms of volumes, or added value.

In terms of volumes, for oil, we will consume less in road transport, and more in air transport and petrochemicals. Vehicle electrification is under way, but it is mostly the efficiency of combustion engines that impacts the consumption of oil for vehicles. As for the aviation sector and petrochemicals, they are both booming and it is hard to see what would stop them. As for gas, we will be seeing a lot more of it in the marine sector, due to the emission standards of the International Maritime Organization from January 2020, and probably less in heating, industry and electricity, where electrification and energy efficiency will gain market shares over gas.

Personally, I like to think that we will make the “best” possible use of oil and gas – that is for more advanced uses, to make products with higher added value. Lightweight electric cars require increasingly lighter and more resistant plastics. There is the use of high quality lubricants for offshore wind turbines.

Petrochemical building materials will make homes less energy intensive, and so on. Solving the problem of pollution caused by shipping would be a fantastic step forward for the quality of the air breathed by the populations of port areas around the world… and for liquefied natural gas!

I think this is our position for Europe, and to achieve carbon neutrality in general – in terms of added value for society.

How to respond to the climate challenge we face? Can the capture and storage of CO2 be an asset? What about hydrogen?

It is more than an asset, it’s a necessity. Today, the IPCC, the International Energy Agency and the European Commission all agree that it will be impossible to achieve ambitious climate goals without capturing and storing CO2. “Finally”, is what we would want to say! Now the message must be passed to the political level, and then to the public: it will take much more than wind and sun to solve the problem, and the solution would require a complex mix of technologies and changes in practices.

CSC has long been presented by NGOs as a way for the fossil fuel industry to stay alive in a carbon neutral future. In fact, storing carbon is becoming a necessity for many other sectors, in particular the cement industry, the iron industry, and the chemical industry that emit CO2 in their industrial processes. It will also be a necessity to cancel certain emissions that cannot be avoided – for example methane emitted by the agricultural sector, carbon emitted by aviation, etc. That’s why we’re calling for a broad cross-sectoral coalition to promote CSC in Europe – we need to overcome our communication gap, and our sector is ready to act.

As for hydrogen, it has become the word of the day in energy and climate talks. Everyone is talking about “green hydrogen” produced from renewable electricity. The problem is that we do not have enough renewables, that it is extremely expensive to produce, and that the volumes are and will remain microscopic for a long time. The reverse is mere fantasy.

If we want to promote the emergence of a hydrogen market in Europe, we must capitalize on current production, based on natural gas. The concern is that currently the CO2 produced by this process is now released into the atmosphere. By decarbonising natural gas, that is, by separating and storing the carbon it contains and keeping only hydrogen, we can provide large-scale low carbon “blue hydrogen”. This would open up a European market, create an ecosystem and a hydrogen value chain and facilitate the integration of “green hydrogen”, the production of which will remain more local and intermittent.

To conclude, how do you think all these points are perceived by the Member States in the preparation and implementation of their National Energy and Climate Plans?

It just so happens that we have done a long analysis of the first drafts of the National Energy & Climate Plans to figure that out, and it turns out that the whole thing is currently pretty much in sync with the idea we have.

We were pleased to see that half of the Member States (14) have a positive view of Oil & Gas Exploration & Production, mainly for reasons of security of supply and as an alternative to coal. Only France mentions the ban on E&P…! This will only accentuate our trade deficit but also our emissions, since the gas produced in the country emits on average 25% less CO2 than the one that is imported. This dogmatic and unilateral measure is therefore meaningless, especially for the climate, for which it is even counterproductive!

As far as gas is concerned, its role in the heating, electricity generation, transport and, to a lesser extent, industry sectors seems clear until 2030.

Member States are also almost unanimous on the need to deploy CSC and hydrogen in Europe, with the notable exception (and here also totally dogmatic and groundless) of Luxembourg for CSC. Many see this as a solution to the problem of industrial CO2 emissions. Only five Member States, however, see the link between natural gas and hydrogen – we still have a lot of work to do on this subject!

With regard to oil, we were perhaps a bit surprised at the extent to which Member States share our point of view on its future role in Europe: The improvement of thermal engines, the role in petrochemical production, the progressive replacement of fuel oil in the heating sector – this is a fairly pragmatic picture of national plans.

Pragmatic yet ambitious and progressive – that’s how I would describe these plans. It will be necessary to take the helm and not fall into outrageous oversimplification, into anti-science, into emotionalism and ideology. It will be necessary to respect each other, to listen to each other, to explain things, and above all to take thoughtful, rational and consensual decisions. Our industry understands, adapts and accompanies the changes our societies are going through – I invite those who do not see it yet to take a closer look.

International Association of Oil & Gas Producers

Av de Tervuren 188A,

B-1150 Brussels, Belgium

www.iogp.org